The J-Head Story: A Collaboration in RepRap Hot-End Development#

After months of working with my RepRap Mendel in the spring of 2010, I found myself constantly fighting the same battle: keeping the extruder working reliably. The hot-end was easily the weakest link in the entire machine. Temperature swings of ±20°C were common, jams were frequent, and the existing designs required tedious assembly with nichrome wire wrapping and careful application of fire cement.

As I wrote to Brian in June 2010: “The current extruder design is definitely the weak point of the RepRap. Most of my problems have been extruder related; I think the only other problem I had was one slipping gear on a stepper that I fixed by adding a set screw.”

That’s when I connected with Brian Reifsnyder, a talented machinist who was already making precision PEEK thermal barriers and brass nozzles for the RepRap community. Where I brought electronics expertise and software development skills (particularly PID control tuning, the feedback loop that maintains stable temperatures), Brian brought precision machining knowledge and a drive to create better hot-end designs. This complementary skillset would lead to one of the most widely used hot-ends in the early RepRap community: the J-Head.

The Hybrid Thermal Barrier Concept#

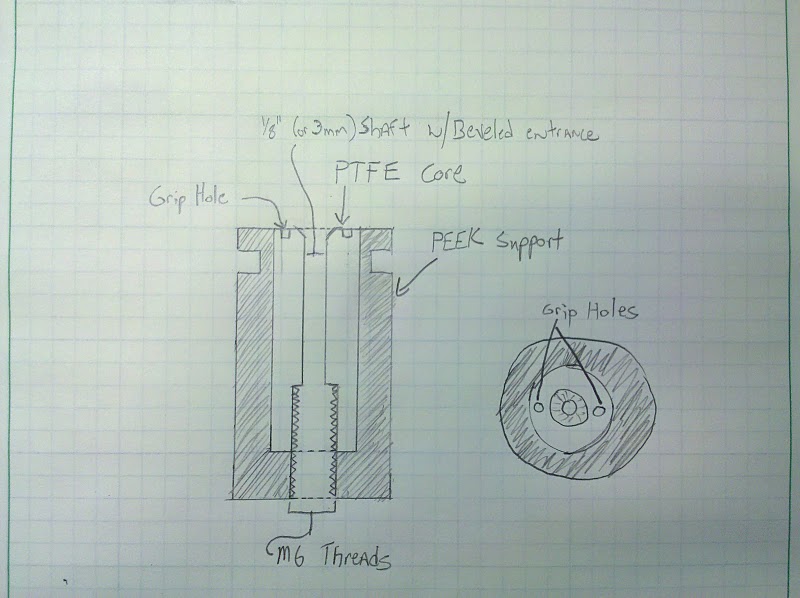

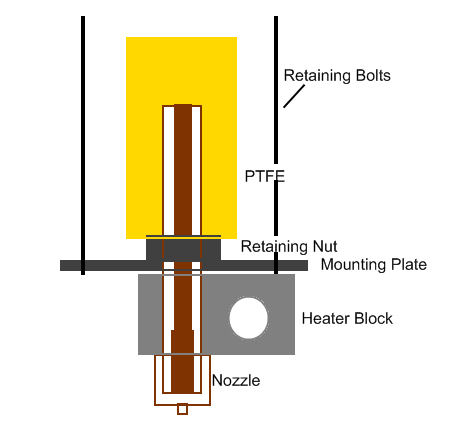

In early June 2010, I was struggling with overheated PEEK thermal barriers that would eventually fail. I’d been experimenting with a hybrid design that used a PTFE core sleeved inside a PEEK support structure. The concept was straightforward: use PTFE (Teflon) where it touched the filament for its low friction and non-stick properties, but use PEEK (a high-temperature engineering plastic) for structural support, since PTFE is too soft on its own.

On June 14, 2010, I sent Brian a rough sketch of what I had in mind. I’d actually built a crude version myself by tapping PTFE (which didn’t work very well because I wasn’t a machinist). The sketch showed a PTFE core running through the center, held in a PEEK sleeve, with some grip holes to help tighten the assembly.

Brian’s response came quickly: “I can make one of those. The grip holes may not work too well as PTFE is too soft. I’ll see if I have enough PTFE tonight.”

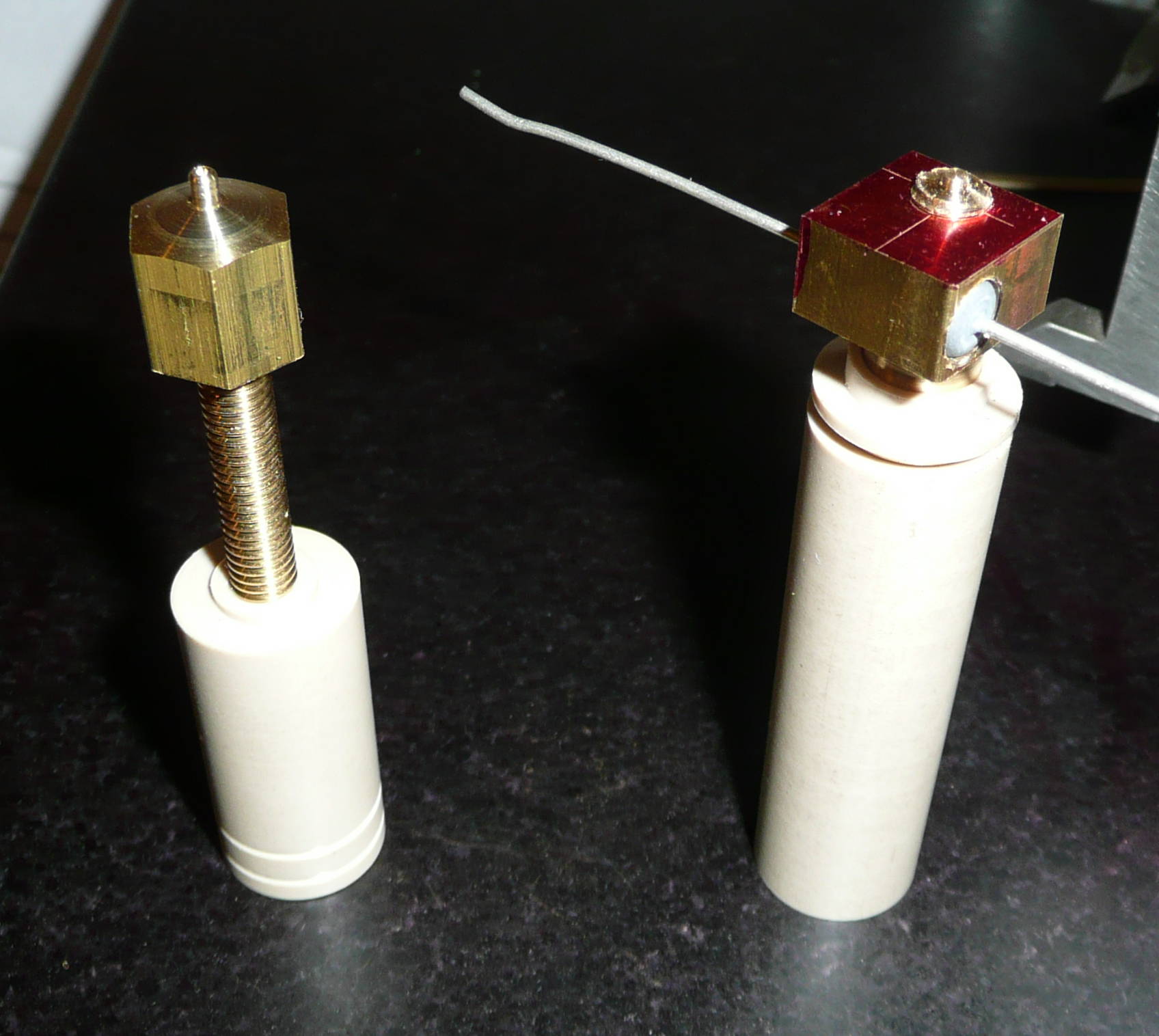

Two days later, on June 16, 2010, Brian had already machined the first hybrid thermal barrier and shipped it to me. Instead of the grip holes I’d sketched, he’d cleverly used a set screw to keep the PTFE core from rotating. This was classic Brian: taking a rough idea and immediately improving it with his machining expertise.

The Heater Resistor Discovery#

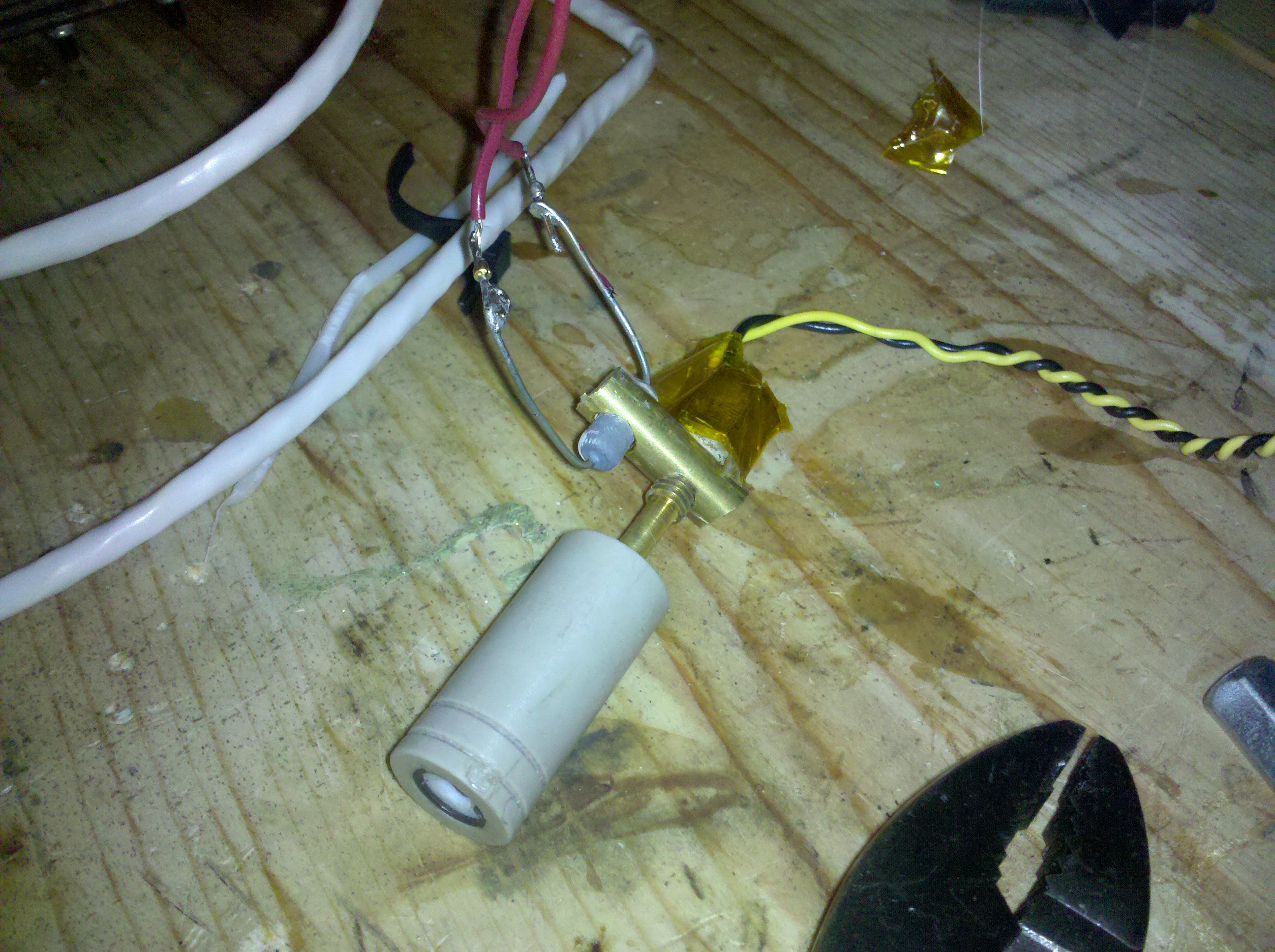

Around the same time, I’d been experimenting with solid-state heater cores as an alternative to nichrome wire heaters. Wrapping nichrome wire was tedious and prone to shorts, and I wanted something simpler and more reliable. I found a power resistor from Digi-Key (part number UB5C-5.6-ND) that could be directly attached to a small brass heater block. It was compact, ran at the right voltage for RepRap electronics, and generated plenty of heat.

By mid-June, my testing had proven the resistor approach worked well. On June 16, the same day Brian shipped the hybrid thermal barrier, I sent him the Digi-Key part number for the heater resistor. At the time, I didn’t realize how significant this would become. That little resistor would become a core component of the J-Head design.

In his email on July 15, 2010, Brian wrote: “Do you mind if I mention your name as to being the guy who found the right heater resistor?” I was honored. This was the spirit of the early RepRap community: crediting contributions and building on each other’s work.

Design Evolution: Simplicity Through Collaboration#

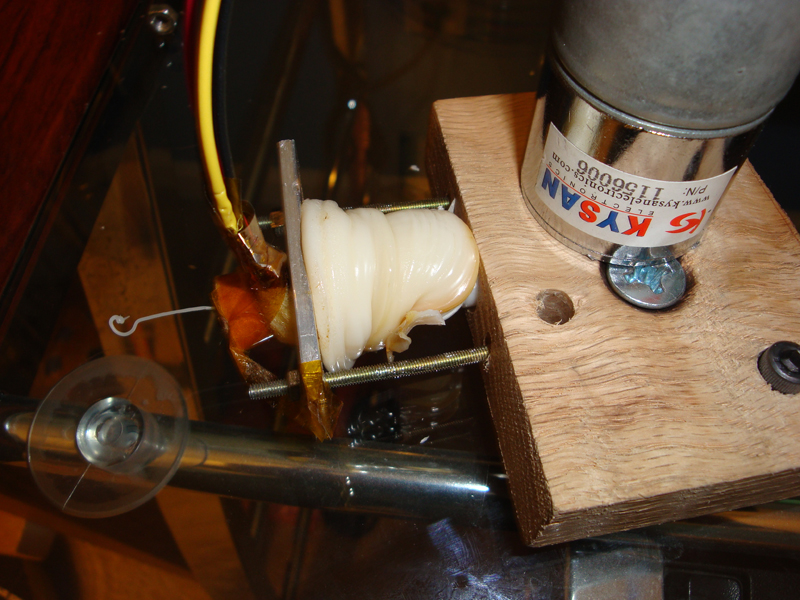

Through June and early July 2010, Brian and I exchanged ideas rapidly. I was dealing with massive temperature oscillations due to the larger thermal mass of the heater block, working on PID control tuning in the firmware. Brian was iterating on the mechanical design, creating what he described as a hybrid of various extruder concepts but dramatically simplified. His approach was methodical: “I figure that I’ll start in the direction of making the nozzles as perfect as possible.”

On June 28, 2010, Brian sent me a message: “I got some time, last night, and made up a heater module using one of the heater resistors you sent me. It is a small, square, piece of brass about the size of a Starburst candy.”

By June 30, he was already moving away from the complex “top hat” design used in other extruders and eliminating the steel mounting plates. The goal was a streamlined design: fewer parts, easier assembly, and better reliability.

The design that emerged was elegant in its simplicity. Internally, it was practically identical to the MakerBot Mk5, with a PTFE liner running the full length from cold end to nozzle tip, but externally it was more straightforward and less expensive. No fire cement required. No extensive kapton tape wrapping. Just precision-machined components that fit together cleanly.

Testing and Real-World Use#

I received my first J-Head prototype in July 2010 and immediately put it to work on my Mendel. The temperature stability was dramatically better than what I’d achieved before. Where I’d previously seen ±20°C oscillations, I was now getting ±3-5°C. Part of this was the improved PID tuning I’d been working on, but part of it was simply having a better-designed hot-end.

On May 22, 2011, Brian announced that the J-Head had been added to the RepRap Wiki at http://www.reprap.org/wiki/J_Head_Nozzle. By this point, multiple people were testing prototypes, including Tony Buser, and reporting 30+ hours of successful printing. The design was proving itself in the real world.

By August 2011, after over a year of extensive testing, I wrote to Brian: “I just wanted to let you know that the J-Head nozzles are both working excellently! This design amazes me. I don’t think I have had a single jam using any plastic in either of them.” It was a night-and-day difference from the constant troubleshooting I’d dealt with before.

Pursuing “State of the Art”: The Aluminum Development#

In August 2011, something interesting happened. Someone asked Brian if the J-Head was “state of the art.” He told me later: “I replied that I really didn’t know what nozzle was state of the art and gave an explanation of the nozzle. The other night, I was thinking about this and decided that I really ought to pursue making it ‘state of the art.’ So, I did some research and purchased some aluminum.”

This kicked off an intensive development sprint. Between August 18-19, 2011, we exchanged nine emails in a 24-hour period as Brian worked on reducing the weight and improving the design. As he wrote to me: “My current ultimate goal, in the RepRap world, is to build the current ‘state of the art’ in open source hot-end design. It needs to be reliable, light, small, and easy to use. It also needs to look good.”

The results were impressive. The original brass J-Head nozzle weighed 11.1 grams. Brian’s new version, machined from 2024 aluminum alloy (a high-strength aluminum), weighed just 3.8 grams, a 66% weight reduction. As Brian put it: “This nozzle is so light it almost feels like it isn’t there.”

He also experimented with fluted PEEK thermal barriers for additional weight savings, though the fluting was time-consuming to do by hand. The complete hot-end assembly came in under 15 grams total weight. The temperature stability improved even further, holding within ±1°C instead of the previous ±3-5°C.

A lighter extruder carriage meant less moving mass, which meant higher print speeds and better print quality. When someone asked Brian if the J-Head was state of the art, he didn’t just answer; he made it true.

The J-Head became one of the most widely used hot-ends in the RepRap community. Brian’s relentless pursuit of excellence, from the initial hybrid thermal barrier design through the aluminum optimization, turned a good idea into a genuine innovation. That’s the power of collaboration: someone with deep machining expertise, driven to create the best possible design, working with community members sharing problems and solutions. That’s exactly how open source hardware should work. Thanks, Brian, for making the RepRap community better.